The 5 Best Pavilions of the 2024 Venice Biennale

Claire Fontaine, “Foreigners everywhere,” Arsenale, ph Marianna Reggiani, The Italian Art Guide;

The fear of being unable to “see everything” often accompanies visitors who cross the threshold of this most anticipated artistic event in Italy and beyond. During the first day of opening, the Giardini and the Arsenale of the 60th Venice Biennale welcomed almost 9,000 enthusiasts, giving rise to months of reviews on the “best and worst” pavilions to provide the public with the necessary means for an itinerary that allows them to “see everything” that matters, without wasting time.

One might ask, however, whether there is also a less frenetic way to enjoy the contemporary art concentrated in the lagoon in these months—a type of entertainment that allows for the waste of time, admits the impossibility of “seeing everything,” and focuses on what the Biennale Arte has to say in 2024.

Curator Adriano Pedrosa’s choice of the title “Foreigners Everywhere” for this Biennale is a bold reclaiming of art’s contemporary role. It’s about bringing together, mixing, and joining. The title, inspired by the ready-made by the duo Claire Fontaine, which in turn appropriated the name of the Turin collective “Stranieri Ovunque”, encapsulates the complexity that has always characterized the process of “making art.”

The artist is a nomad by definition, even when they remain still. They are often a political victim, a migrant, a refugee, a traveler. A natural consequence is that art is never pure but always the result of mixtures, contaminations, and infestations.

Once you have crossed the gates of the two splendid entrances, it might be worthwhile to dwell on this: on feeling like foreigners, forgetting what is ours and what is someone else’s, because other people’s stories are always, inevitably, ours too.

It would be worth wasting time rather than trying to “see everything.” The knowledge and insights gained in this way, the memories that stay with us even after we leave the pavilions, are far more significant than a list of countries ticked off with a pencil.

This is how we approached our journey to the Biennale: not as a race to see everything, but as a contemplative experience. This is the time we “wasted,” and this is what we took away with us.

Entrance to Venice Biennale 2024, ph Marianna Reggiani, The Italian Art Guide;

Japan, Yuko Mohri – Giardini

Water, light bulbs, fruit. Like a curious laboratory, the pavilion focuses on cracks, decomposition, and defects. Yuko Mohri addresses the theme of floods—a plague that has always threatened Venice—drawing on various expedients adopted in Tokyo subway stations to stop water leaks. “Moré Moré (Leaky)” is an installation in which the liquid leak, caused voluntarily, is healed through various and unusual expedients: boots, bottles, basins, and plastic tanks, which are the members of an orchestra of arcane, sometimes disturbing, sounds and movements. As observers, we are left at the mercy of the objects that govern the space: undisputed protagonists of a scenario in which the human presence is only a spectator, they seem to speak, to feel emotions, to have lives of which we know nothing.

In the interactive ‘Decomposition’ installation, electrodes are inserted into various fruits, turning them into living bodies in a state of constant transformation. These fruits dictate changes in sound and light intensity, with decomposition, aging, and deterioration setting the pace and rules for the evolving environment.

In a room that seems governed by pure magic, everything tends instead towards a more human principle than ever: adaptability. In a historical period torn apart by global crises, tormented by conflicts, unbridled capitalism, and solitude, Yuko Mohri proposes, with subtle irony, to start from there: from what is wrong, from what has broken over time, that continues to deteriorate over time, that has lost light, shine and value, that is about to be thrown away. It is not a simple recycling operation—which would also have a lot to teach us—but an awareness that we can’t face contemporaneity without getting in tune with its most profound, disastrous, tragic defects.

Yuko Mohri, “Compose,” 2024, installation view, Japan Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia, ph kugeyasuhide; courtesy of the artist, Project Fulfill Art Space, mother’s tankstation, Yutaka Kikutake Gallery, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery;

Uruguay, Eduardo Cardozo – Giardini

It’s the pavilion of silence, where a whisper echoes, and every step is a shock. In front of “Latente,” the installation by Eduardo Cardozo, there is space for three: the visitor, the artist and Tintoretto. As soon as you enter, you are absorbed by the cumbersome vision of a dance of colors floating in the air: it is Cardozo’s homage to the “Paradise” of the great Venetian master, who here lives again through the draperies and volumes of his blessed subjects, welcomed in the lagoon by a religious silence. The overwhelming effect is immediate; the overbearing color devours the space that surrounds it, just as the authentic fresco dominates, a few kilometers away, the hall of the Maggior Consiglio of Palazzo Ducale. Tintoretto is in front of us, with his foaming clouds of fabric, the chorality of his composition, and the harmonic twists in the sign of the most rampant Mannerist tradition. And the place is so intimate that the encounter with the master is one of the most spiritual, sacred, and collected. The master is pawing the ground under the color and would almost like to speak. The observer remains there, waiting for a sigh from the fabrics.

The installation continues on the left wall of the pavilion, on which Cardozo exposes himself—laying himself bare—through pieces of his atelier, transferred thanks to the technique of detachment. The operation is complex in its totality—it makes materials, supports, techniques, colors, and spaces speak—but disarming in its simplicity: it is the confidence of an artist, his most intimate secret suspended in the air.

To complete the environment, a large fabric composed of scraps of gauze sewn together is placed on the last wall, where it was used to transfer the walls of the artist’s studio.

Eduardo Cardozo, “Latente”, Uruguay Pavilion, ph Marianna Reggiani, The Italian Art Guide;

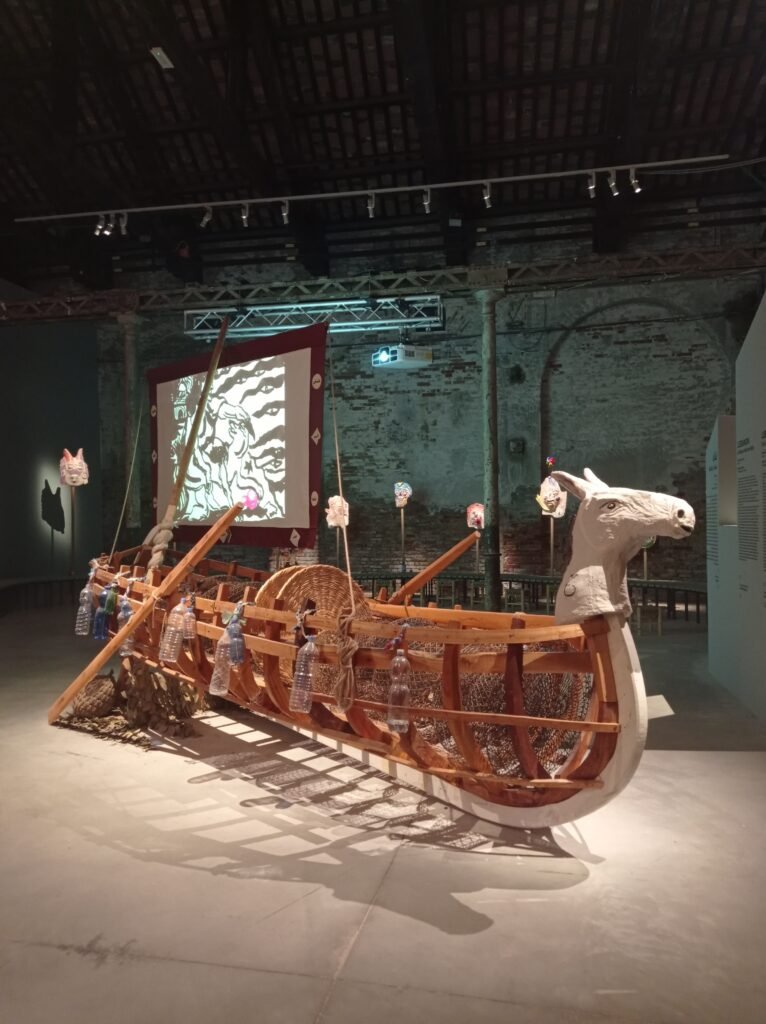

Lebanon, Mounira Al Solh – Arsenale

While walking along the beach of Tyre, Princess Europa was kidnapped and enslaved by Zeus, who was fascinated with her and disguised himself as a white bull. The female condition in Greek mythology is the channel through which the artist Mounira Al Solh invites us to reflect on the possibility of overturning the predominant narratives, in which the woman suffers the legitimacy conferred to the male “divinities” to dispose of her. The possibility exists, and the exhibition “A Dance with her Myth” wants to lead us precisely there: to new and unexplored ways of telling stories, experiencing society, and conceiving politics.

Mounira Al Solh starts from afar, from a young Phoenician (today Lebanese) woman who bore the name of what is now our present: Europa was a slave, a conquest, a trophy. Mounira Al Solh wonders if it still has to be like this today, if it is not possible to take hold of the anger and pain of millennia and transform them into something more powerful, that does not destroy but teaches, that does not contaminate but educates. The stories we listen to end up defining us: the artist then rewrites, imagines, distorts, to redefine herself as an individual and redefine us as a society. “A Dance with her Myth” is a gentle invitation to participate in a non-violent protest, a peaceful resistance based on redefining the stories we have always loved so much, which is now high time to let go.

Mounira Al Solh, “A Dance with her Myth,” Lebanon Pavilion, ph Marianna Reggiani, The Italian Art Guide;

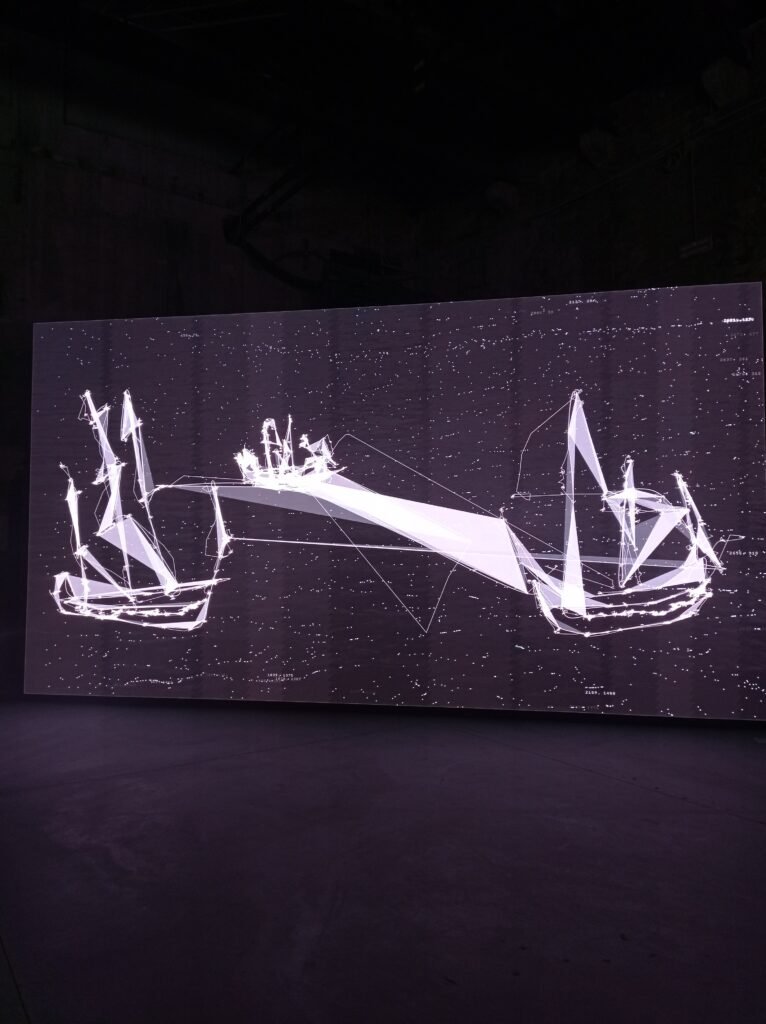

Malta, Matthew Attard – Arsenale

Starting from the ships rudimentarily drawn on the ancient facades of Maltese churches, the installation “I Will Follow the Ship” by Matthew Attard intertwines drawing, intended as an expression of faith and cultural identity, with new technologies. Thanks to an eye-tracker, a huge screen shows the slow delineation of the outline of a ship, drawn by the movement of the artist’s eyes. Thus, the gaze becomes a creative act that is distinctive to each individual.

The mural drawings of the past—traces of anonymous and never-recognized artists—communicate with a present forced to deal with prevailing technology and the danger of automation. Therefore, the symbol of the ship is the key to understanding: an element that unites, touches, and travels the most remote spaces of the earth. Sometimes, it resists time, becoming a bridge between peoples, places, and historical periods, drawing possibilities and challenging risks and dangers in order to build new neighborhoods.

From the sailors of the past to the migrants of today, Attard recalls the journeys undertaken with hope in their hearts. After all, if we are “Foreigners Everywhere,” it’s precisely because a ship has taken us to distant lands.

Matthew Attard, “I Will Follow the Ship,” Malta Pavilion, ph Marianna Reggiani, The Italian Art Guide;

France, Julien Creuzet – Giardini

The pavilion in which the artist invites the spectator to enter and “go with the flow” is a labyrinthine jungle. Through the wake of the matoutou falaise—the typical tarantula of the island of Martinique, in the archipelago of the Lesser Antilles—a microcosm of colors and sensations unfolds before the eyes of the observer, devoid of interpretation codes. The installation is, therefore, a stimulus to create associations and free thoughts and write stories not yet told. The one narrated by Creuzet—the mystical vision of the arachnid in the darkness of a tropical forest—calls us to discover our own, unique and singular: “You might come face-to-face with anything, including yourself.” The observer is invited to make a clean slate, to accept—perhaps with difficulty—the lack of clear indications to enjoy the work in favor of a creative and imaginative push that takes him far away, where only he can go. A few steps into the forest are enough to understand how to proceed and with what spirit and gaze. You can emerge confused by the chaos of colors or invigorated by the richness of images of associations, with the new awareness that someone else’s stories can become, for us, an invaluable resource.

Julien Creuzet, “Attila cataracte ta source aux pieds des pitons verts finira dans la grande mer gouffre bleu nous nous noyâmes dans les larmes marées de la lune”, France Pavilion, ph Marianna Reggiani, The Italian Art Guide;

Translation to English: Dobrosława Nowak