WHO’S GOOD BOY?

Reasonable Chaos

Often my job requires me to write introductions to contemporary art exhibitions, something I take pleasure in doing, turning a deaf ear to, or rather, not looking for answers to, the question about whether these text are actually any use, as the answer would certainly be no. I personally think that a text about an exhibition would be more constructive after its inauguration, a few days after it opened. You could call what I am about to write a pre-text, something that happens before and thanks to my privileged position as curator, which gives me the opportunity to see the works and have long conversations beforehand, but it could also be called a pretext: one I use every time to understand how and what every artist and every single artwork produced, have to offer, that something which is specific to everyone that sees it, feels it or touches it.

“WHO’S GOOD BOY?” is the provocative and evocative title of Sebastiano Pallavisini’s first solo exhibition in his hometown (Udine, Italy,1999) with which SMDOT/Contemporary Art is happy to start its fifth year of research and programming. “good boy” is an expression used to gratify a pet, in most cases a dog, for behaviour that conforms to human expectations. In our case, the animal, amazed and unaware, wonders: “Who’s Good Boy?”. Starting from this simple and ironic question, where subject and object, adjective and proper noun are tangled up and confused, with a grammatical change between lowercase and uppercase letters, Sebastiano Pallavisini, with wit and irony, shifts and modifies our conventional points of view. Most of the works in the exhibition are new: medium and large paintings, sculptures and drawings. The artworks trigger an aesthetic struggle with human beings and their presumption in evaluating and judging, compelling and inviting us to rediscover a new, almost primordial relationship with nature, encouraging us to see ourselves as an extension of the world around us. As the philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour said, there is no external environment, and we must become aware of this in order to begin to consider how interconnected we are with each other and with all other forms of life, and learn to modify our actions.

We might suggest that the conceptual framework underpinning Sebastiano Pallavisini’s work reflects a conviction expressed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the mid-eighteenth century, who asserted at the height of the Enlightenment, that man is born good but is corrupted by civilisation, which, together with the abuse of his faculties, make him unhappy and evil. …” O Man! seek no further for the author of evil; thou art he … (J.J.Rousseau, Emile or Education, Book 4). Sebastiano Pallavisini’s painting and sculpture plunge us into the artist’s struggle between primordial chaos, evil, clichés and looming catastrophe. He abandons the power of sight in favour of touch, inviting us to join him in prioritising what we feel over what we see. He repays our efforts with images that do not resemble reality, with figures that we seem to recognise, but do not know. The works in the exhibition do not illustrate, they do not show us the known visible world, they do not depict. Instead, they face the chaos, they bring it to the canvas, drawings, and sculptures. They try to dominate it, with hands, with the body, with the brush, the spatula, rags and paint. Before the fall from the great heights expressed in the works, before the arrival of an imminent catastrophe, for a brief moment, we can see the invisible forces that are hidden among things, that are the cause of our continuous movement and therefore the continuous possibility and hope for change.

Words written on the page or said out loud find it hard to describe the invisible, but this is no reason not to try. They have a linear progression, they might change tone or intensity, but regardless, they follow a path, they occur one after another. Sebastiano’s work is an aesthetic practice that is undertaken in depth on several planes at the same time. These planes are always precariously balanced, where a chaotic, tragic, and sometimes violent movement is given just a touch of wit. Perhaps it is precisely his way of using this ironic wit that lets us into his work. In the images in the exhibition we can see dogs, wolves, lynxes, wild boars, bears, and bonobos… but are they really animals? What habitat do they exist in? What are they really doing? The viewer becomes like the dog who hears himself called “Good Boy”, and wonders, quite disoriented, Who is “Good Boy”? What is going on? What am I doing? Why am I being called? What will the consequences be? Which is the right way to go? How do I become a good boy? Clearly there are no unambiguous answers, but we can benefit from the power of sharing experiences, as often happens in a place where you can meet up physically in the presence of works of Art, a special place where you can disagree with each other and enjoy non-confrontational and non-polarising conversations about our differences.

This kind of space seems to have disappeared completely from our daily lives. Increasingly our critical abilities are eroded, replaced with simple and functional solutions, buffeted by an infinite number of defined and determining images. Art, the work of art, is never resolved or determining, it is never finished or defined, there is always something missing. It is always poised between chaos and the possibility of catastrophe, which can give us an insight beyond the known, the already-seen, the already-created, that permits this moment of balance. Sebastiano Pallavisini’s works also use a degree of irony that can be seen in the titles. These make us uncomfortable, forcing us to move from Descartes’s “cogito ergo sum” to the “sentio ergo sum” of Aristotle, thus shifting the focus from the rational to the perceptive dimension, bringing us back, with irony, to what is reasonable.

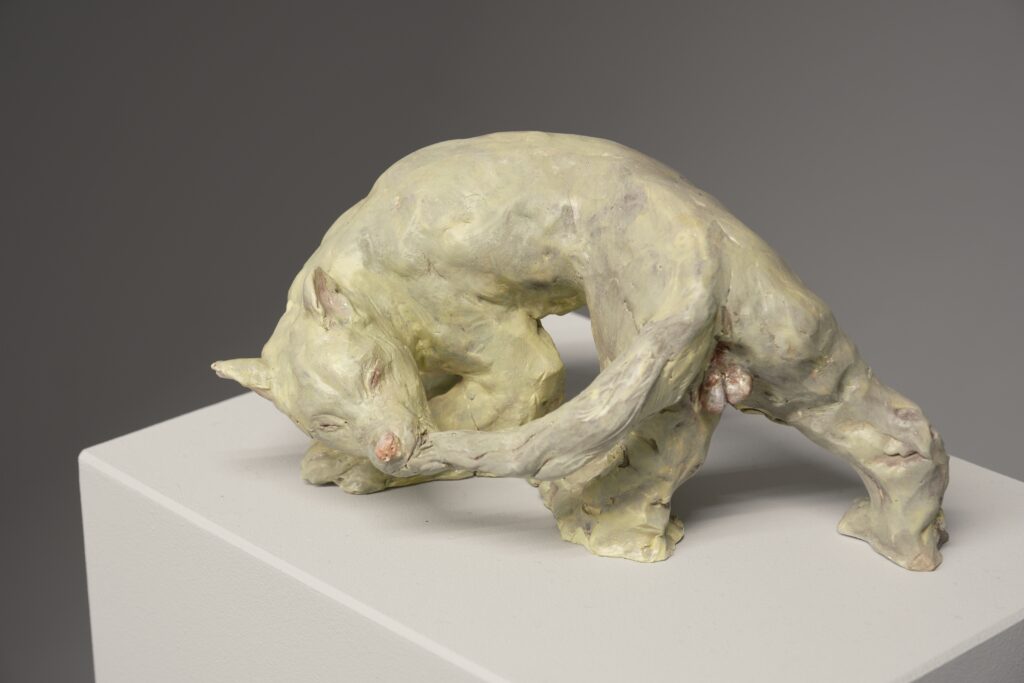

In this way “Brodino Primordiale, bruciato” (series, 2025, eight drawings, Repap mineral paper, ecoline ink, 25 x 17.5 cm), calls to mind the colour and warmth of hot broth (brodino), a classic comfort food for winter evenings, transporting the body to our chaotic origins of the primordial broth in the title. Territorial pissing (2025, oil and acrylic on canvas, 150 x 130 cm) depicts the struggle for territory, it is the struggle for one’s own space, it is the pride that overcomes the love for oneself, there are animal bodies (?), emptied, out of balance, in a false equilibrium. “Ocio!”, (2024, glazed ceramic, 30 x 25 x 10) is the head of a bear (perhaps) it stares at us from one point of view with one glass eye, and with the other invites us to reflect. “The orangutan gang”, (2024, oil and acrylic on canvas, 200 x 300 cm), shows us the potential violence of a group and the risks of induced polarisation, but also the possibility of escaping from it, in this case through colour and gesture. “Bonobos”, (2024, acrylic and oil on canvas, 200 x 190 cm), is as deceptive as they are deceptive, they look like us, and are sad, perplexed, perhaps smiling, perhaps trying to suggest something. “Good Boy” (2025, glazed ceramic, 25 x 15 x 10 cm), looks just like a dog, although personally this resemblance does not convince me, he is biting his tail, and is clearly not happy, he is in pain or is bored, I like to think that he is bored.

The hope is that this boredom, this going round in circles, but above all, the self-induced pain of the bite, can metaphorically shake us out of the compulsion to act at any costs and the constant acceleration of life. By painfully stopping the circle, we can learn to listen, which is a form of inaction where the ego, which is normally busy with differentiations and delimitations, falls silent. “Good boy” is the voice of the individual who tries to seek and discover his identity in the other, which is where things fade and mingle together, the world shines in a friendly tangle, and an emotional translation is made in this “reasonable chaos”, a classic instrument of the work of art (perhaps).