3 Exhibitions to See in February

Our guide to exhibitions in Italy

02.02.2026

Among the perhaps most surprising powers of visual art is its ability to show, in ever new ways, that behind the most personal forms of expression there almost always lies a collective feeling.

Inspiration, need, intuition may be the prerogative of the individual, yet their origins often take root in a shared ground—a public soil.

The desire to dissect language and its most microscopic elements is not so distant from the attempt to imagine a world without domination or the sense of conquest: different eras, media, and sensibilities are still capable of expressing the same concerns and anxieties.

The three exhibitions selected for February are an invitation to rethink the time and space we inhabit, how we move within them, and which relationships we choose to prioritize. They are an attempt to spark new debates, to take part in the public discourse, and to heal the ever-widening gap between the collective and the individual.

Nanni Balestrini. La rivolta illustrata – Galleria Frittelli arte contemporanea, Florence (until 22 April)

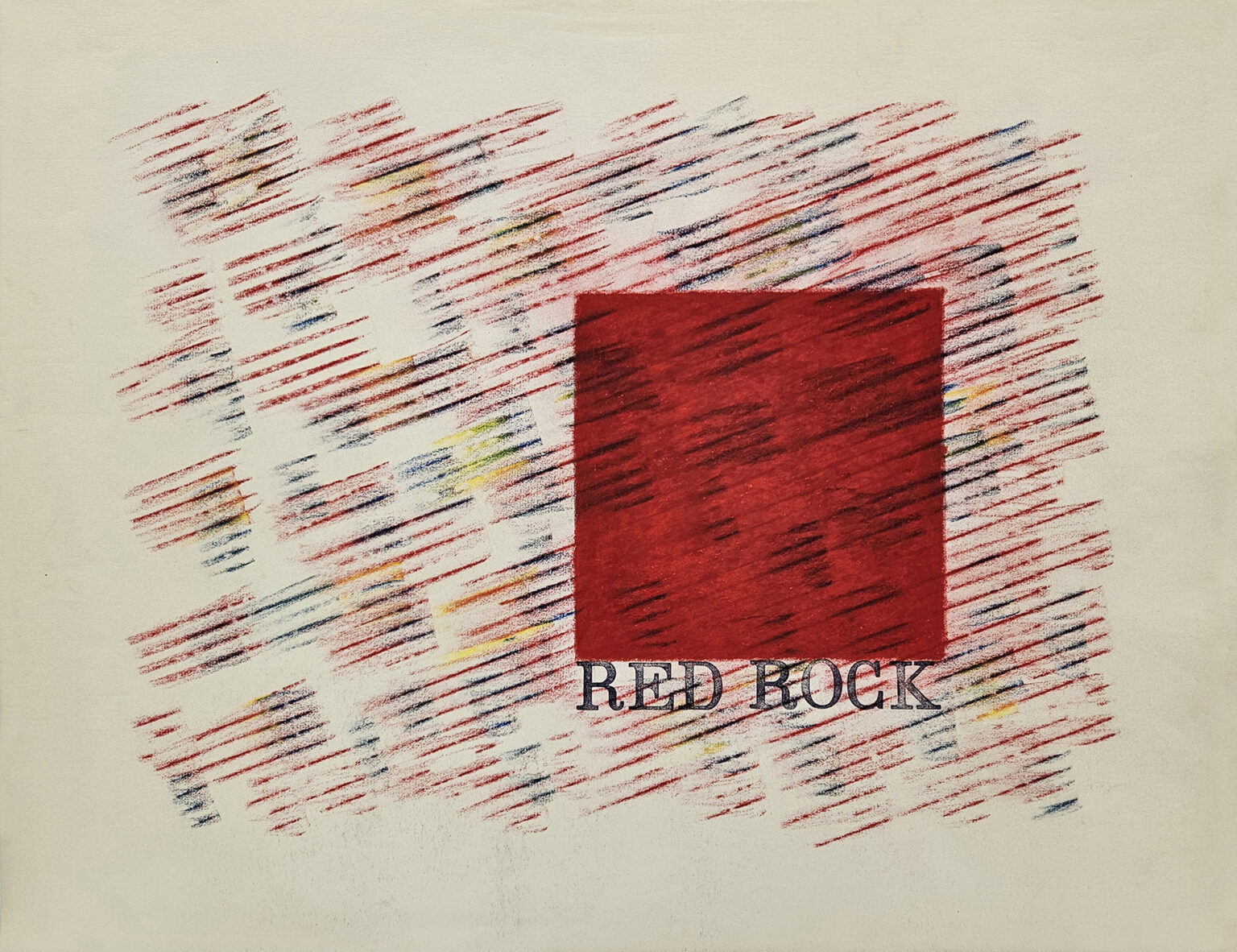

Nanni Balestrini, Ondulé: Red rock, 1981. Credits Galleria Frittelli arte contemporanea

Nanni Balestrini regarded words as if they were living beings, endowed with personalities, biological rhythms, and distinctive traits. He cuts them, dismantles them, breaks them down, and reassembles them into constructions made of signs and punctuation—distinctive elements isolated against a background—in a kind of continuum between verbal and visual language.

At the root of the exhibition’s title, curated by Marco Scotini, lies the novel La violenza illustrata, published by Einaudi in 1976, in which Balestrini uses words to evoke images, fully exploiting the visual potential of language.

In the works on display, by contrast, words—and letters—shrunk, enlarged, stretched, repeated, inverted, torn apart, become images themselves. In this interpenetration, in this uninterrupted flow between the visual and the verbal sphere, lies the artist’s understanding of the autonomy of language: a living body, mutable and vibrant.

One of the protagonists of the neo-avant-garde and a key figure within Gruppo ’63—alongside, among others, Umberto Eco and Renato Barilli—Balestrini took part in the Venice Biennale in 1993 and in Documenta 13 in Kassel in 2012.

Today, celebrated for the third time with a solo exhibition by the Florentine gallery, the Milanese artist—who used “words as images and images as words”—is brought back to life seven years after his passing through a selection of over one hundred works, largely unpublished. Ranging from collages to plastic materials, the exhibition presents an irreverent body of work that, resistant to constraints, has thrived on its tireless experimentation.

All That Changes You. Metamorphosis - Palazzo Te, Mantova (until 31 May)

Isaac Julien, All That Changes You. Metamorphosis, installation view. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro and Jessica Silverman. © The artist. Photos: Andrea Rossetti / Palazzo Te

“A joy for the eyes and a feast for the mind”: this is how the film installation resonating through the monumental spaces of Palazzo Te has been described. For the first time in Italy, Isaac Julien pays homage to the architectural complex that symbolizes Italian Mannerism—an edifice imbued with an atavistic sense of death and destruction, yet at the same time overflowing with life and color.

Inspired by the philosophical work of Donna Haraway, the British artist’s film is an invitation to rethink space, the planet’s resources, and our way of being in the world—to “abandon the idea of a privileged human subject”1 (Stefano Baia Curioni, Director of Palazzo Te) in favor of a universal gaze aimed at a necessary transformation that concerns the entirety of contemporary life.

Architecture and environments play a fundamental role within the film, from Californian forests to the pavilion housing the Kramlich Collection. The climax, however, is reached in the Sala dei Giganti, the masterpiece frescoed by Giulio Romano between 1532 and 1534. There, where everything collapses, where all is annihilated by the unbearable weight of the cosmos, space opens up for change. It is precisely in that space, as Curioni again observes, that our “task of accepting that problems exist” resides. “Our intellectual and artistic vocation is not to deceive ourselves, but to look at the reality of things, which is made of transformation.”

VIVONO. Arte e affetti, HIV-AIDS in Italia. 1982-1996 - Centro Pecci, Prato (until 10 May)

VIVONO. Arte e affetti, HIV-AIDS in Italia. 1982–1996, installation view, ph Andrea Rossetti

VIVONO isn’t a story of a pandemic phenomenon. It is a composite exhibition that doesn’t function as a closed system but is activated through interaction with an external gaze. It is a tool in which subjectivity and collectivity occupy the same space and resonate equally, because one does not exist without the other.

Works of art, poems, soundscapes, and videos—alongside archival materials and personal memories—trace what unfolded from 1982, the year the first case of AIDS was reported in Italy, to 1996, the year antiretroviral therapies became available. For the first time, the history of the most stigmatized disease in contemporary history is told within an institutional exhibition through the voices of Italian and international artists affected by the HIV crisis. The posters by Gran Fury, as well as works by Keith Haring, Nan Goldin, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Porpora Marcasciano, do not speak about the disease itself, but about the “generative moment”2 it represented—the network of relationships and organizations that translated intimate, private love into political and public action. This is a history that already forms part of the identity of Centro Pecci and its permanent collection Eccentrica, in which the theme of HIV is central.

The exhibition thus takes shape as a generational narrative; it invites viewers to empathize with those who suffered, dwelling on the dual pain caused by contagion and by a solitude not chosen, but violently imposed by a part of the world that insisted on defining itself as “healthy.”

________

1 Stefano Baia Curioni, Direttore Palazzo Te

2 Press release

Translated to English by Dobroslawa Nowak