3 Exhibitions to See in December

Our guide to exhibitions in Italy

Di Marianna Reggiani

02.12.2025

Clicca qui per leggere questo articolo in italiano

December is the month of happiness at all costs. You can find it discounted in stores, for pennies at market stalls, covered in glitter in the most refined shops. It seems everyone buys it and wants to show it to you, proud and smiling, on your feed at the end of the day.

Like being trapped in a cage, there seems to be no escape, as if we were all forced to witness this emotional massacre, to participate in a competition we never signed up for.

Wandering through exhibitions remains one of the few things that still allows us to feel connected to ourselves, to our curiosity, our tiredness, and our dissonance with the outside world. Free to understand or not understand, see or not see, linger over an artwork for five minutes or an entire day. If enjoyed honestly, art is full of choices that set us free.

As every month, here are three exhibitions that ask for nothing except understanding. In return, they ask nothing of you but, precisely, complete and disinterested honesty.

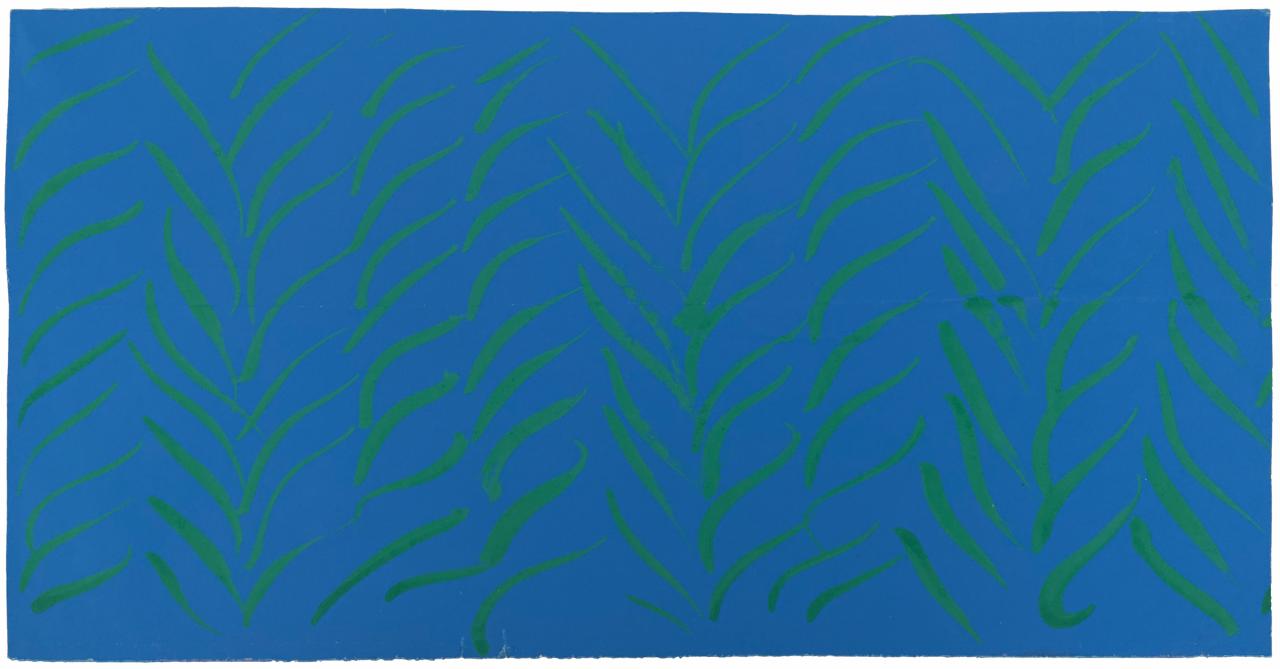

Carla Accardi. Segni dell’anima #2 – Galleria Lombardi, Rome (from 6 December 2025 to 10 January 2026)

She painted on the ground. One hand rested on the floor, the other gripping the brush as it ran across the canvas. Carla Accardi worked with this pose for years, giving form to “the vital impulse present in the world,”1 reiterating the wonder of creation through the act of painting, imbuing the brush with a primordial, generative power.

It is this centrality of the sign that Galleria Lombardi wishes to celebrate by dedicating the second and final chapter of the Segni dell’anima project to Accardi, inaugurated with an exhibition dedicated to Antonio Sanfilippo. The artistic partnership between the two, married in Rome in 1949, represents one of the most significant events of European abstract art in the second half of the 20th and early 21st centuries.

Repetition and variance are the key elements of Accardi’s research: the repetition of abstract signs emulates the mechanisms of material reproduction; the variance of each sign, at the same time, reflects the natural principle whereby every product is unique and distinct from the others. Her compositions explore black and white, color, surfaces, and materials, probing matter itself, the space it occupies, and its proliferation across the canvas. In this way, Accardi weaves an ode to the world she inhabits, to the nature that governs it. ‘The path was mind, arm, and sign,’2 without interference.

With twenty-five works spanning the 1950s to the 2000s, the exhibition showcases the Trapani-born artist, the only female signatory of the Forma group’s manifesto, a feminist activist and co-founder of Rivolta Femminile, and a middle school teacher suspended from her position because of a conversation about the condition of women held with her female students: Superior and Inferior. A Conversation Among Middle School Girls remains a manifesto of disobedience to this day, recently returned to the shelves thanks to Crackers Books.

Luigi Ghirri Polaroid ‘79-‘83 – Centro Pecci, Prato (until 10 May 2026)

A simulacrum of a slowness that we evidently miss today, the Polaroid has returned to our bags, on the walls of our bedrooms, in our feeds, a reminder of a melancholic vintage that we wish would save us from digital dictatorship.

For Luigi Ghirri, however, Polaroid was a true experiment to explore the uncertainty of the photographic medium: invited to Amsterdam—the company’s European headquarters—to test the 20×24 Polaroid, the artist framed objects, landscapes, and streets with an eye that managed to see their soul, breaking through their shell—a philosophical exercise, or perhaps simply his natural way of looking.

The indefinite, nuanced and transparent patina makes his subjects immortal ghosts, with soft contours and rounded corners: they are dreams, the visions that are kept in the last drawer at the bottom of the wardrobe.

The artist thus finds himself recounting an intimate daily life in a foreign land—Holland—while remaining so viscerally connected to his Emilian mists. The almost carnal connection to the land that Giorgio Morandi—and no one else like him—reflected in his painting, Ghirri declared through his photographs, revealing himself as a poet even before being a visual artist, capable of narrating time that stands still, the extraordinary instant in which the moment is captured or let go forever.

The chapter of Ghirri’s life exhibited at the Centro Pecci, curated by Chiara Agradi and Stefano Collicelli Cagol, is a parenthesis in his work that often goes unnoticed yet encapsulates the pillars of his photography: the ambiguity between absence and presence, honest intimacy, and an ever-open heart.

Male extinction – Galleria Solito, Naples (until 8 January 2026)

Five international artists—Sitara Abuzar Ghaznawi, Nora Aurrekoetxea, Caterina De Nicola, Eva Gold, and Miranda Secondari—question what a future without the male gender might be like. They do so with good reason, as recent genetic research suggests the Y chromosome is undergoing deterioration, making it natural to wonder what kind of future awaits us.

This summer, New Scientist magazine published the discovery of a team of Spanish archaeologists who, in 2008, recovered the remains of the so-called Ivory Man, considered the most powerful man in prehistoric Iberian history. In 2021, after a careful analysis of the tooth enamel, the discovery shocked the same team: the human who dragged those bones now reduced to almost nothing was an “Ivory Lady.” That body, buried more than five thousand years ago next to a rich ivory collection, a sign of respect, reverence, and extreme power, belonged to a woman. Not a man, as long thought, because it was easier, more intuitive, and more spontaneous.

The “re-sexing” operation carried out by the team of archaeologists, therefore, tells us that women in prehistoric times were rulers, warriors, hunters, and shamans, and controlled land, money, and family.

The five artists, invited by curator Massimiliano Scuderi to dialogue at the former Wool Mill, a UNESCO World Heritage site, engage in a rediscovery of “an innate and wild Self that the surrounding culture has outlawed.”3 An exercise in imagination, but more than that: it is a reflection on one’s own possibilities, on one’s place in a new world where risks—such as being raped, beaten, or killed—are diminished and relationships with others are changed—since the other is no longer there.

Aware that in such a world their destiny is extinction, the five artists play with symbols, pop culture, gender roles, and clichés. Their installations—wigs, industrial kitchens, worn men’s shirts, knuckledusters embedded in the wall—thus invite us to overturn dominant perspectives, to reclaim attributes historically reserved for men—power, strength, self-sufficiency.

In short, they invite us to think of ourselves as the Ivory Lady even when everyone is convinced that she doesn’t exist.

________

1 From the catalogue of her solo exhibition at the Galleria San Marco in Rome, 1955

2 link

3 Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Jungian psychologist

Translated to English by Dobroslawa Nowak