5 secondi

Of Fiction and Falls, Tricks and Accidents

Serena Schioppa

The Chewing Gum

“I am writing this with a black ‘Tempo’ fibre-tip pen. A few months ago, I bought fifteen of these pens for sixty pence. Unfortunately, because they are so common, other people pick them up, thinking they are theirs. I bought the pens from a market in Kingsland Road in Hackney, about a hundred yards from where the film was shot. The film draws attention to the cinematic codes and illusions it incorporates by denying their existence, treating representation as absolute reality.”

Slowly move the trailer to the left / and I want the little girl to run across now.

These are the opening lines of The Chewing Gum, a 16mm film by British artist John Smith, shot in 1976. It was inspired by the 1973 French film Day for Night (La Nuit Américaine) by François Truffaut, considered one of the first examples of metacinema. Unlike Truffaut, in The Chewing Gum, John Smith remains behind the scenes, never appearing on screen. His voice directs the movements of pedestrians, animals, cars, and everything that comes to life on the screen, orchestrating the bustling activity of a busy intersection near a cinema in Hackney, London. Smith hides behind the camera, using the combination of voiceover and image to transform the documentation of an everyday moment into something artificial. Even when the tone shifts, and the viewer realizes Smith is dubbing a real-life scene after the fact, the film’s narrative drive encourages belief in the illusion, convincing the audience that the artist is genuinely directing the pigeons or the hands of a clock.

In Day for Night, Truffaut appears within the frame, visibly directing extras on a crowded street while making a film. In 5 seconds, Martinucci operates both inside and outside the scene. He appears on-screen, not as a director like Truffaut, but as the main actor. He stands still, holding a bag, in a small portion of space captured in an unusual vertical framing from above. It could be a square, with paving that resembles an animal-print pattern. The bag in his hands, we will later discover, is full of oranges. The bag eventually breaks, spilling its contents onto the ground. The street is not very busy; three figures briefly appear in the background before quickly ceding the scene to our sole actor.

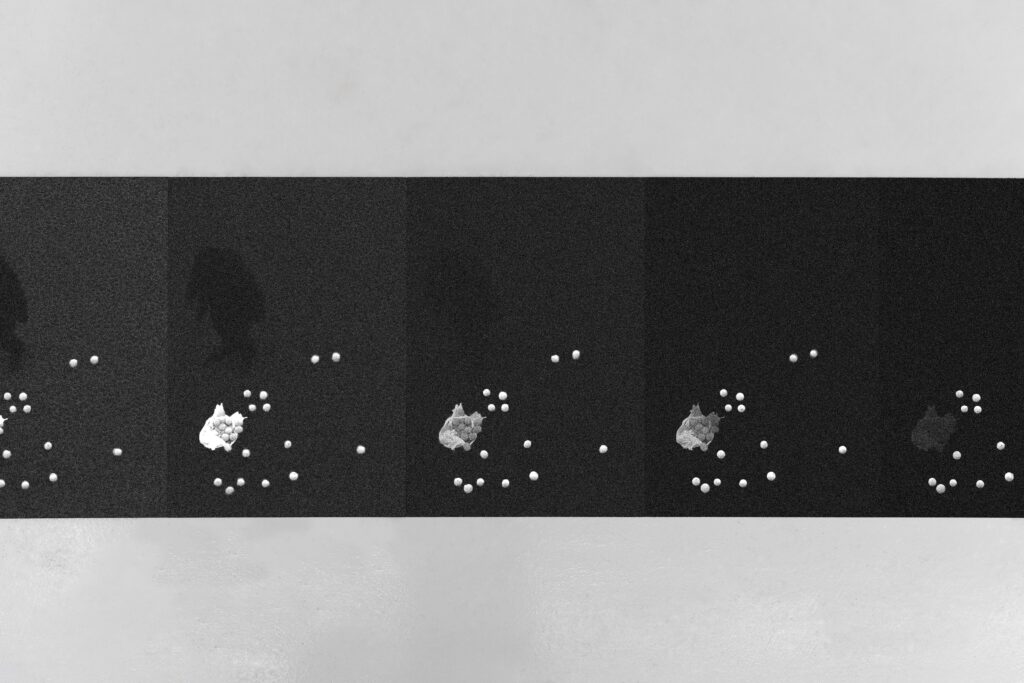

Martinucci is also behind the scenes but behaves more like a traditional director than Smith. While Smith appears to guide the scene without actually doing so, Martinucci directs it, rehearses it, changes settings and accidental extras, and refines it until he achieves the images accompanying these pages. For instance, here he might appear with a passerby, with two passersby, or perhaps alone with the bag. Perhaps the bag has already fallen, or its contents have abstracted from reality into an unexpected constellation against a dark sky. This is what happens in 5 seconds.

If Smith had encountered this scene, he might have described it as follows:

“I want a young man in dark clothing standing at the center of the scene, holding a bag in his hand. / Now, a figure should quickly pass behind him. / Another one crosses the street, walking in front of him. / Now the young man drops the bag from his hands. / Now the bag falls to the ground. / The oranges spill out onto the road. / The young man exits the scene to the left. / Special effects. / We lose all reference to reality. / The oranges resemble a constellation in a dark sky.”

What unites Smith, Truffaut, and Martinucci’s 5 seconds is the notion of fiction: a scene that appears real but isn’t, or a real scene made to seem artificial through voiceover, or a fabricated set within a real scene on a real set. However, the illusion Smith discusses in the opening quote of this text becomes even more pronounced in Martinucci’s work, abandoning cinematic codes in favor of the hyperbolic and absurd, hallmarks of the artist’s oeuvre.

In the final frames of 5 seconds, Martinucci abandons the pretense—never truly pursued—of remaining within a realist language and opens the door to metaphor, to the possibility that something magical or surprising might occur within such a brief span of time.

5 seconds can encapsulate the time it takes for a trick, a fall, a lie, or a metamorphosis.

Anatomy of a Fall

It was October 26, 2023, when the film Anatomy of a Fall (Anatomie d’une chute), directed by French filmmaker Justine Triet, was released in Italian theaters. The film won the Palme d’Or at the 76th Cannes Film Festival and the 2024 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, shared with co-writer Arthur Harari. A thriller, specifically of the legal or courtroom subgenre, the film’s narrative relies heavily on the legal world and its figures: lawyers, judges, and prosecutors. The title echoes another courtroom drama, Anatomy of a Murder, directed by Austrian filmmaker Otto Preminger and released in 1959, which caused a stir for its graphic and unsettling details.

In Anatomy of a Fall, the plot revolves around reconstructing the events of a suspicious death in a mountain chalet occupied by a wife, a husband, and their blind son. As described in the film magazine Nocturno:

“The premise of Anatomy of a Fall is simple; the situation, however, becomes complex: the genesis is a death. A fall. Samuel, an unfulfilled writer, falls from the top floor of the mountain chalet where he lives with his wife, Sandra, and their eleven-year-old blind son, Daniel. Samuel dies. It is the child who finds him, returning from a walk with the guide dog, Snoop. By touching the body, he realizes it is his father. The image of the fall, the director says, was inspired by the famous opening sequence of Mad Men with its falling silhouette. What happened? The man may have committed suicide, driven by a life he considered a failure, or he might have been killed by his wife, with whom he may have been in conflict. The prosecution leans toward the second hypothesis and initiates proceedings to indict the woman and bring her to trial.”

Over its 150-minute runtime, the film seeks to reconstruct the fleeting seconds during which Samuel’s body either slipped or was pushed from the attic window of the mountain chalet. These few seconds bring a radical shift in the lives of those involved. Samuel’s fall is simulated multiple times; models of the chalet are created to study the possible trajectory of his body, and the blood spatters found on the wooden roof are examined against a snowy landscape where scarlet red starkly contrasts with the white of the snow. Hypotheses, suspicions, and doubts drive the story, soon transforming the anatomy of a fall into a meticulous dissection of a dysfunctional relationship that emerges in all its brutal cruelty during the gripping and dramatic trial.

By contrast, the fall in Martinucci’s 5 seconds does not stem from death or tragedy but instead unfolds as a kind of dissection. A single scene, lasting the titular five seconds, is broken down into 120 sheets, isolating and shaping an extraordinarily brief moment. The scene is divided into 120 frames, where, in an imperfect loop, a simple, even mundane action unfolds. We see a bag of oranges slip from the hands of a young man in the foreground and fall to the ground—a fall that does not lead to tragedy but rather opens the door to imagination and possibility.

Martinucci guides us through a metamorphosis that requires step-by-step attention, frame by frame. 5 seconds takes the audience into a space far larger than the brief timespan would suggest, that of the Fondazione Baruchello, which for the occasion transforms into a perfect stage set. The viewer is invited to look down, to follow the traces leading to the fall and its surreal outcome.

As in Anatomy of a Fall, here too, the audience is urged to scrutinize every detail, to uncover what lies beneath an apparent reality. A closer look raises doubts and invites questions about the presumed veracity of the scene—not only in cinematic terms but also in terms of perception, where reality and fiction blur.

We might discover that the 5 seconds displayed in the space underwent post-production, where passersby weren’t truly present at the moment depicted. Or perhaps we’ll notice that some sheets were trimmed more than others to suit the environment. Unlike in films, in 5 seconds, the scene adapts to the stage, making the narrative more plausible yet never entirely real.

This becomes easier to believe when considering the final frames of the action—the supposed constellation mentioned earlier, which seems to float in the air, opening new scenarios where the problem of truth gives way to wonder and enchantment.

Ontology of the Accident

In 2009, French philosopher Catherine Malabou published her essay Ontologie de l’accident in France. The book was released in Italy ten years later by Meltemi under the title Ontologia dell’accidente. Saggio sulla plasticità distruttrice (Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity). In the opening pages, Malabou writes:

“In most cases, lives follow their course like rivers. Sometimes they abandon their bed without any geological reason, without any underground path to explain such flooding or overflow. The force, suddenly deviant and deviated, of these lives is explosive plasticity.”

Using the metaphor of rivers, Malabou describes how an individual’s life, through significant trauma or even a trivial event, can undergo a decisive transformation. From this unforeseen, often traumatic or unnoticed disruption, the individual is forced to assume a new identity, adopting unprecedented forms that, according to Malabou, make a return to the original state impossible. Malabou’s concept of plasticity possesses a transformative and, as she defines it, destructive capacity. Yet, balanced between destruction and creation, the breakdown of one form necessitates the birth of another.

For rivers, new forms might include tributaries flowing into an unexpected sea or minor branches destined to rejoin the main course and arrive at the same destination. For individuals, however, Malabou argues that returning to the original course is not an option. The destructive potential of plasticity can, however, have a creative counterbalance, giving rise to a new individual. This reconfigured being, fundamentally altered, takes on a completely new form—a direct result of the transformative event.

Here, the term form should not be understood literally—as physical appearance—but rather as a state of being. This contrasts with famous examples of metamorphosis, where the change is always superficial, never substantial. Daphne turns into a tree, Gregor into an insect, Proteus into water and fire, but all eventually return to their original form, reclaiming their familiar traits. In most ancient metamorphoses, Malabou emphasizes, transformation occurs in response to danger: when escape is not an option, the being changes its form, but its essence remains unchanged.

In terms of transformation, however, even an encounter with something seemingly insignificant—a harmless animal, a plant, or some fleeting element—could prove equally decisive. Such an interaction might compel us to alter our time, rhythm, direction, and ultimately, our meaning. In 5 seconds, for instance, we might wonder whether the fall of a bag of oranges during an ordinary daily routine could signify something deeper—a metaphor for an inner collapse, a potential radical shift in the current state of affairs.

A fall, a minor accident, might restart the cycle or cause an irreversible upheaval of the status quo. As Malabou writes in the second chapter of her essay:

“The individual’s history is definitively shattered, torn apart by a meaningless accident—an accident that cannot be reclaimed through language or memory. A brain injury, a natural disaster, a brutal, sudden, blind event cannot, by definition, be reintegrated after the rupture it has caused in experience.”

Using Malabou’s language and thought, the fall at the heart of Martinucci’s 5 seconds might be interpreted as the meaningless accident she describes. Martinucci stages the stumble, an unexpected fall with an unforeseen outcome, repeated in an infinite loop. This is, in fact, an impossible feat if we consider that stumbles or accidents belong to the realm of chance—the unpredictable, unforeseeable, and unrepeatable.

The solution Martinucci presents in the displayed 5 seconds is merely one of countless possibilities offered by chance, where fiction acts as a magical agent.

For the viewer, nothing is activated without the behind-the-scenes work of the artist, without an artifice that restores enchantment. This idea recalls certain passages from a book by Genoese anthropologist and researcher Stefania Consigliere:

“When we disqualify their performances as tricks, we reveal the division within ourselves: because every technical marvel in the complicated world around us is, in turn, a trick, a tinkering with reality to circumvent the already given. […] [And yet] the ball that disappears from the magician’s hand catches perceptual boredom off guard and forces us, if only for the duration of the act, to open ourselves to the wonder of the world.”