Bitten by Witch Fever

The body of works within Bitten by Witch Fever reflects on how the naturalization of the use of chemical poisons in pesticides and an ornamental framing of nature interconnect, becoming both ways of concealment of forms of violence towards the other than human. The roots of the research lay on the ubiquitous indoor presence of arsenic during the Victorian Age. Arsenic, besides its already established legacy as a deadly poison, alongside being implied at the time in rat poisons, insecticides and herbicides, it was also largely used in cleaning products, cosmetics, dyes, health tonics and a range of beauty products, such as complexion soaps and wafers. The spread of a brighter lighting systems in the nineteenth century, first through gaslight and later electricity, transformed how domestic interiors were perceived and decorated. As rooms grew brighter, the demand for vivid wallpapers, fabrics and paints grew bigger. As well as fruit and vegetables were sprayed with arsenic-based insecticides such as “Paris Green,” named after its use to kill rats in the sewers of Paris, the very same material was implied in dyes for household decor for its vibrant tone of green. The use of this toxic element was so naturalized it acquired domestic ubiquity. Strangely, few people seemed able to make the connection between rat poison, or insecticides containing arsenic, and the arsenic used for other day-to-day purposes. The new arsenical pigments fitted perfectly into the Victorian taste for nature-inspired decoration. Wallpapers and fabrics in brilliant greens and blues conveyed class, taste and moral order. Manufacturers such as William Morris dismissed doctors’ warnings as hysteria. “Doctors were bitten as people were bitten by witch fever,”

The Victorian arsenic epidemic offers an eerie parallel to the hidden chemical exposures in our homes today. 80% of people’s pesticide exposure today occurs indoors: within the simple act of breathing up to a dozen different chemicals from household air, stored in the dust, are absorbed by our bodies. In 2024, scientists from Madrid’s CIEMAT analysed 128 dust samples from European cities. These dust samples contained a median of 57 different pesticides each, many of them banned for agricultural use in Europe for decades, but persisting in indoor dust.

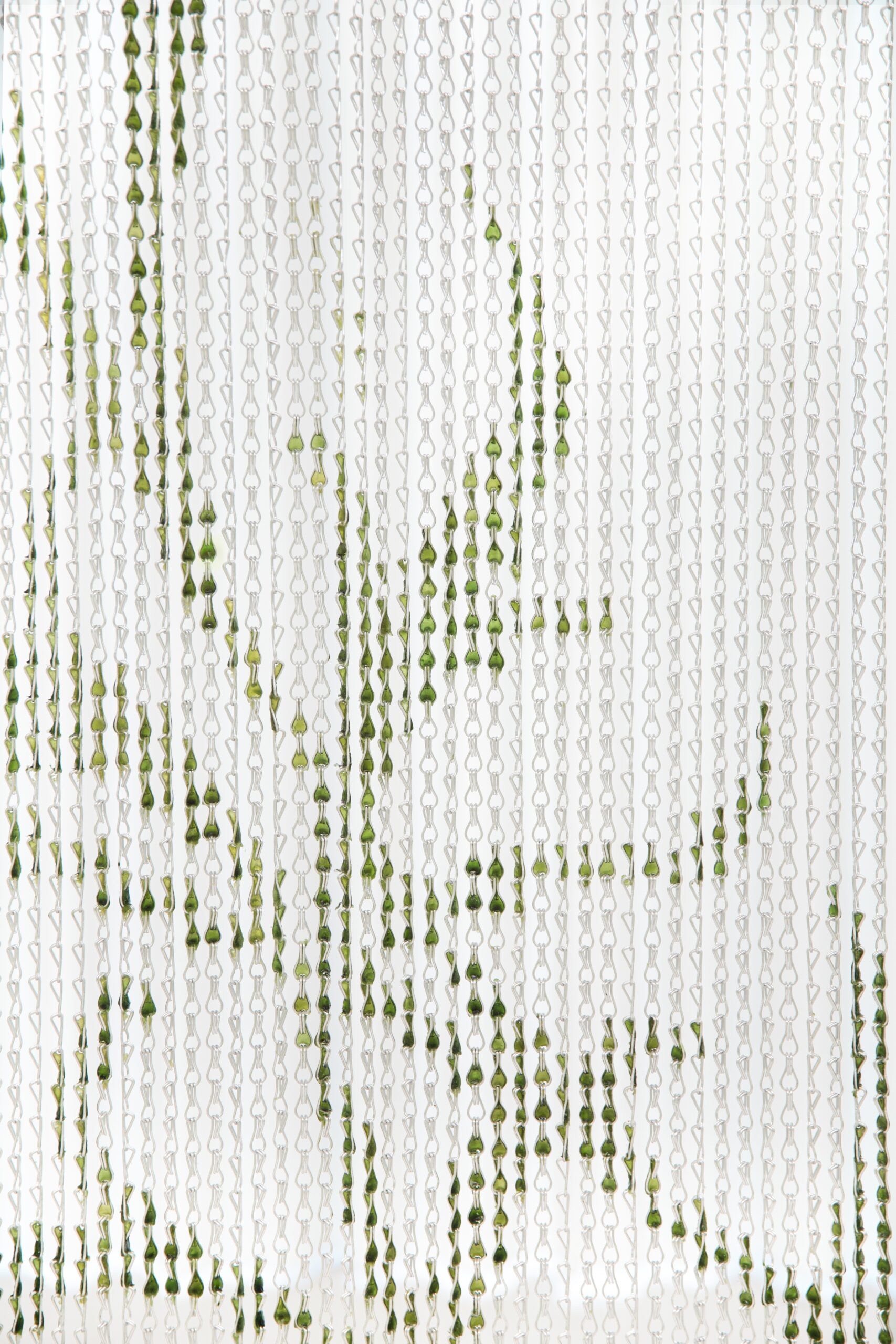

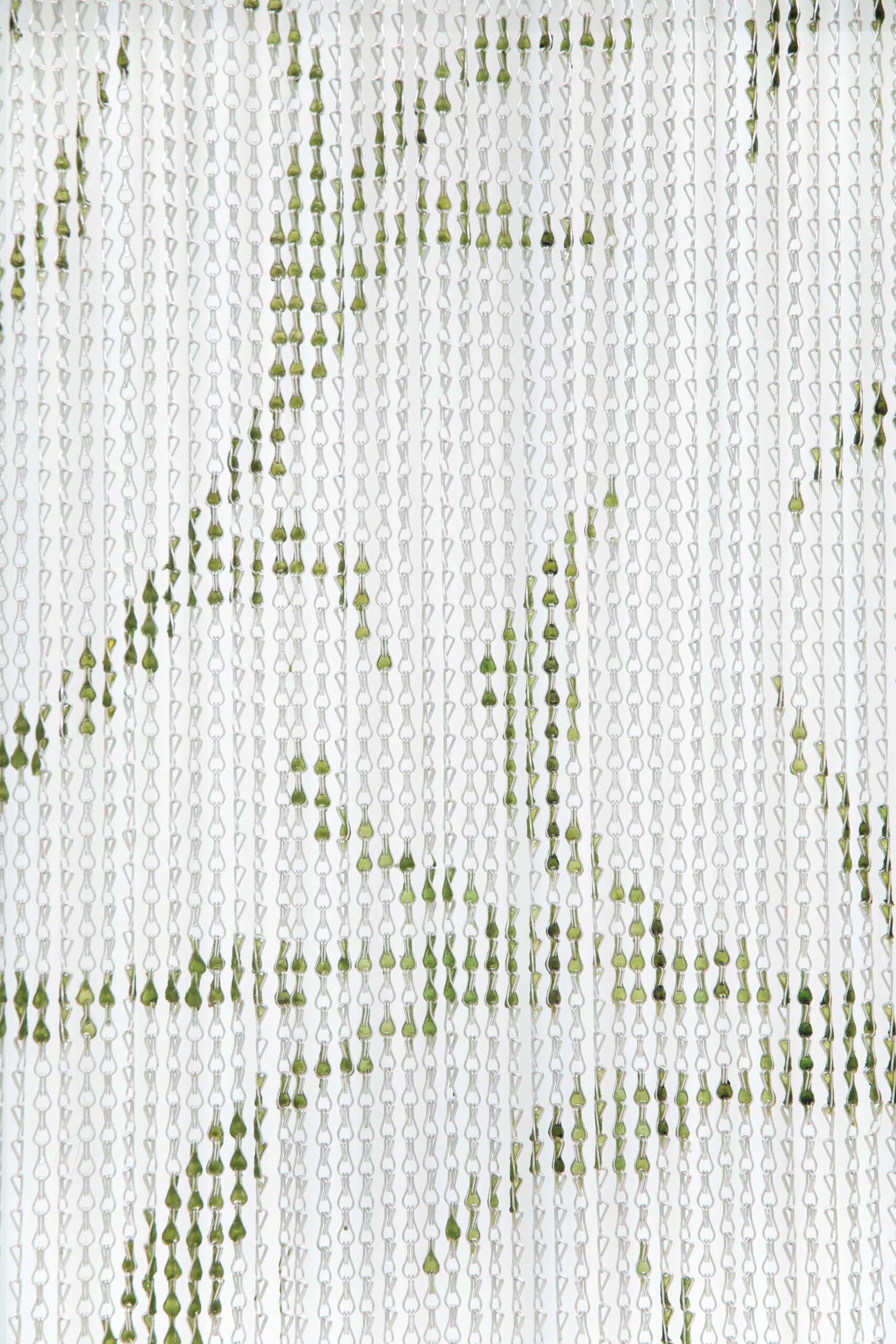

Mundane insect repellent tools and materials become the vehicles through which reflect on our hostile forms of relations that have been naturalized with these crawly creatures. An insect-repellent aluminum curtain is adorned by pesticide soap gems, whose pattern, reproduced only in its green parts, is a detail from the “Scroll” design by William Morris, one among many that has been tested as arsenic positive. An ephemeral dust carpet on the floor is the 1×1 reproduction of “Montreal Natural Jade” rug by Morris. The green parts of the original design appear made of the powder from mosquito repellent spirals. Lastly, a chandelier-like lamp comes down from the ceiling. The original lampshade has been replaced by the same aluminum chains that compose the insect-repellent curtain, and its acid-yellow light is conferred by an anti-insect LED bulb. What commonly attracts insects into our homes, here emits a special spectrum of colors of 560-580 nm wavelength, called “twilight light”, that is instead projected to repel them. What appears banally mundane, decorative or ornamental, reveals, or unveils, its silent tensions.