I was real

Péril en la demeure. The need to act quickly.

by Eva Foucault

Andrea and I talked about moving and how we like to pack our lives into boxes. There’s something about

control in the miniaturization of our surroundings. A need for closeness, too. Having everything within reach, to stay connected to our daily lives, to feel reassured.

As a child, I thought I could be very helpful during moves by taking care of the “small things.” Tiny furniture, little chairs. A matter of ladders and dimensions: anything less than 50 cm high that could be carried up the stairs.

Later, we were burgled. A proper burglary. The door torn off its hinges, every drawer opened and overturned onto the cushioned beds. That memory of something so systematic and frightening haunted me for years.

How can one be as discreet as possible? Make no noise, erase any trace of presence, even while turning everything upside down? Burglary is deeply tied to memory — to the loss of an object, or the image we had of it. And of course, is rooted in a primal fear of letting someone, or something, uninvited into our home.

Later still, my father installed a system of “intelligent” mechanical shutters — a well-rehearsed automation, remote-controlled, designed to simulate our presence during holidays. At fixed hours, alternating on a schedule, the shutters would open gradually. First the ground floor facing the living room, then the bedrooms upstairs. I now see a kind of sad absurdity in that system, trying to (re)enact our rhythms of waking and sleeping. There’s also a certain violence in the idea of the house as a fortress protected from “intrusion.”

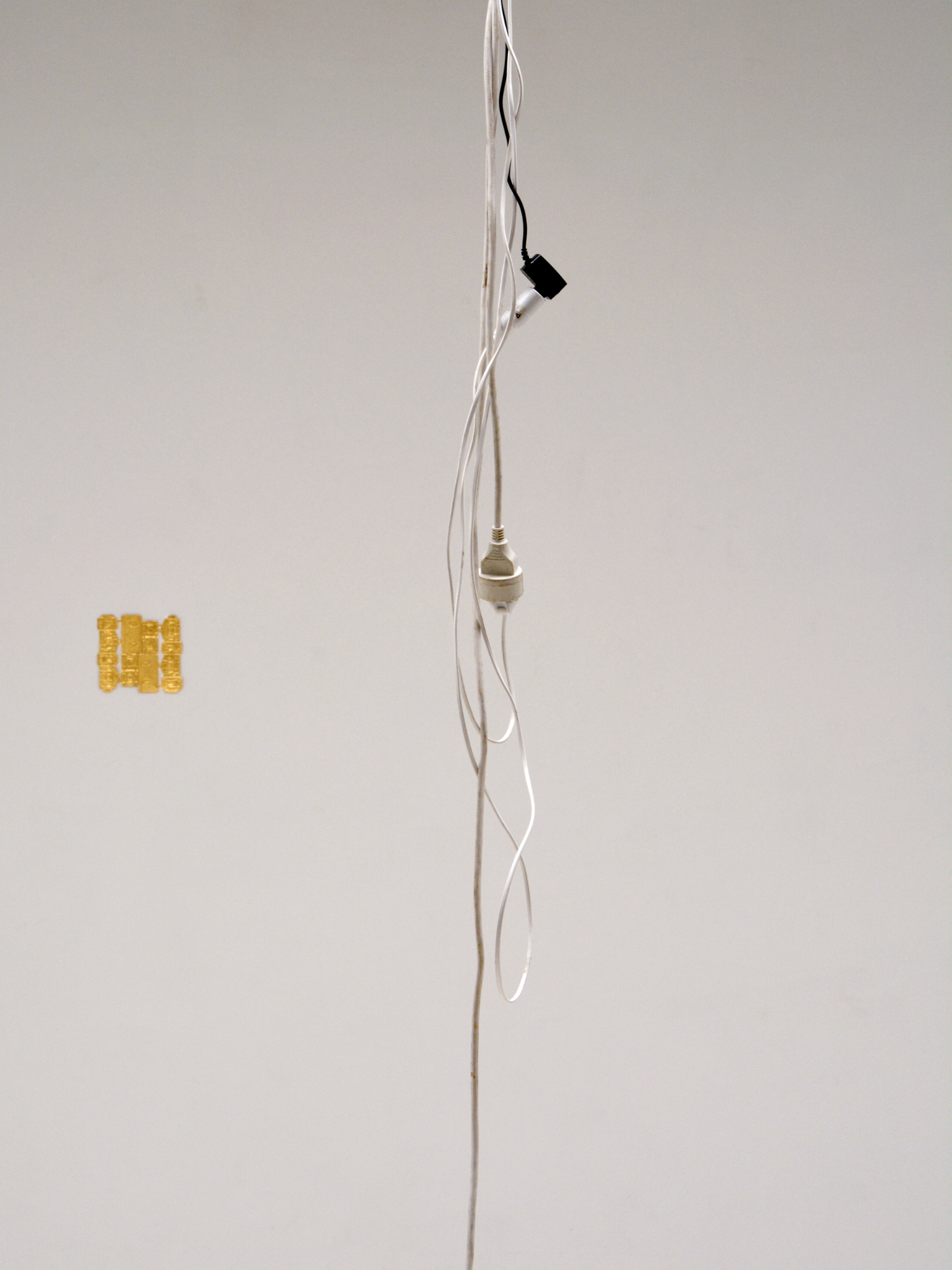

Andrea Spartà also inhabits his own “secondroom” of absent residents. Set on an infinite loop, a lamp randomly projects flashes onto one wall. This anti-burglary gadget bought online says a lot about the emptiness of our lives: it imitates us, represents us, through the luminous noise of a fake TV. There’s something disturbing in this setup. It evokes both the abstract static of CRT screens — the idea of an image without an image — and Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019), where false presence becomes a trope of contemporary domesticity. Showing what we’d rather not see. Revealing the possibility of an other in a space we believe controlled. This feeling of overflow in my own home manifests physically, in the tangle of cables bursting from their boxes.

A profusion so intense it becomes a kind of oversharing — telling so much about ourselves that everything spills over, leaks out, and floods others with too much intimacy. A kind of breach born from too much exposure.

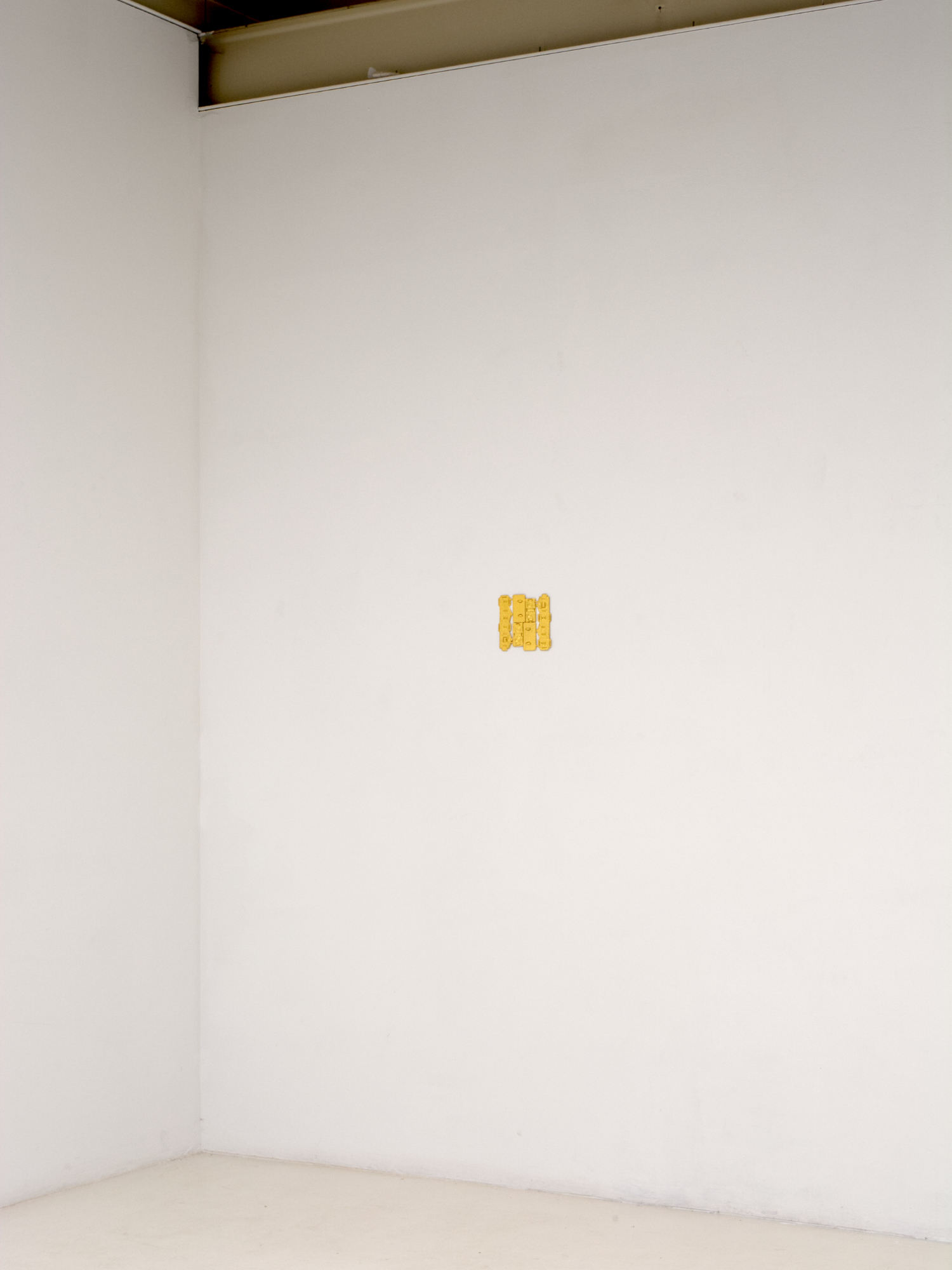

This domestic monster faces off with the perfect image of home. Gilded, these fake Christmas chalets are themselves almost too much — exaggerated representations of “Home”: archetypal, shiny, gingerbread- scented Christmas ideals. Something supposedly comforting and serene. And yet, in our minds, these scale models were actually there. “I was real,” “J’étais réelle,” I existed once. For me, that I once was, in image overlaps with the idea of what our homes could be. It’s located in the moment of choice, that first arrival when everything is still possible. A lingering image we try to grasp again.

***

I’m struck by the double meaning of the word demeure. To dwell is to be there, in the present of a given space-time. The dwelling, as house, fixes that state.

I’m particularly fond of that moment of suspension that comes with inhabiting a space for the first time, when we fumble our way through an empty place. At first, it’s hard to let anything in. Placing an object inevitably sets something in motion — an intention, a way of being. I try to delay that moment as much as possible, to prolong the indeterminacy of possibilities, where a perfect home might still emerge.