Io sono Io. Io sono Me

Galleria Tiziana Di Caro presents Io sono Io. Io sono Me, the fourth solo exhibition by Tomaso Binga (alias Bianca Pucciarelli Menna, Salerno, 1931) held at the gallery, opening on Friday, May 23, 2025, at 11:00 AM.

The project spans the artist’s entire creative time frame, following the thread of writing as a sign or narrative element which, throughout a practice now spanning over fifty years, unfolds in various forms, insisting on a principle the artist has always proclaimed and warded: writing must carry a subliminal intent, it must operate independently of the meanings it expresses or the sounds produced by each word. In this sense, writing becomes “silent writing.”

The title of the exhibition is borrowed from a 1977 work, a photographic diptych in which handwriting is embedded in the image and frames the body through what Binga defines as “living writing.” Io sono Io. Io sono Me is a work where the repeated use of the personal pronoun indicates a reclaiming of subjective identity, autonomy, and independence.

It is precisely this autonomy and independence that Tomaso Binga has embodied throughout her career, never succumbing to trends, but instead advancing with determination and coherence, both artistically and personally.

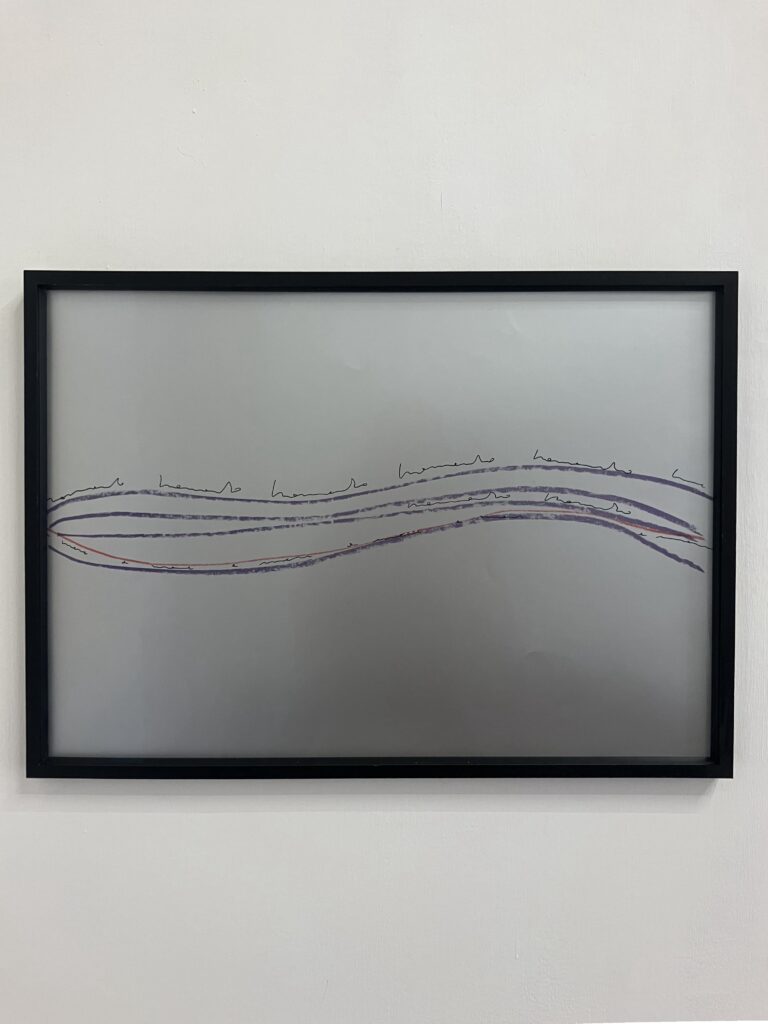

Her first works featuring writing date back to the early 1970s. The artist employs what would later be defined as Scrittura desemantizzata [Desemanticized writing]: a thin, essential sign that manifests itself independently of meaning—indeed, that seeks to hide or even overturn meaning. Desemanticized writing is composed of rough, repetitive marks. The word becomes image, it falls silent, and yet its presence remains constant and perceptible.

In the Ritratti analogici [Analog Portraits], subjects are represented by the initials of their names and surnames, integrated with figurative elements that evoke defining traits of the people portrayed. The letters replace physical features. In the Grafici d’amore [Love Charts], the narrative element addresses the emotional dynamics of romantic relationships.

In some cases, writing maintains its semantic value, though it appears obscured because the script is unclear or illegible, presenting itself more as a mark than a readable text—but with close attention, it can be decoded. This is evident in some of her Polistirolo [Polystyrenes]. Polystyrene has a distinct identity: these are collages on packaging materials, three-dimensional objects that contain images. Many of them also become spaces where writing emerges, expressing concepts. But can desemanticized writing truly describe anything? As Binga herself once said: “Writing is not describing”—a phrase she used as the title of her first solo show with the gallery in 2015. This is the foundational premise that informs much of her creative system.

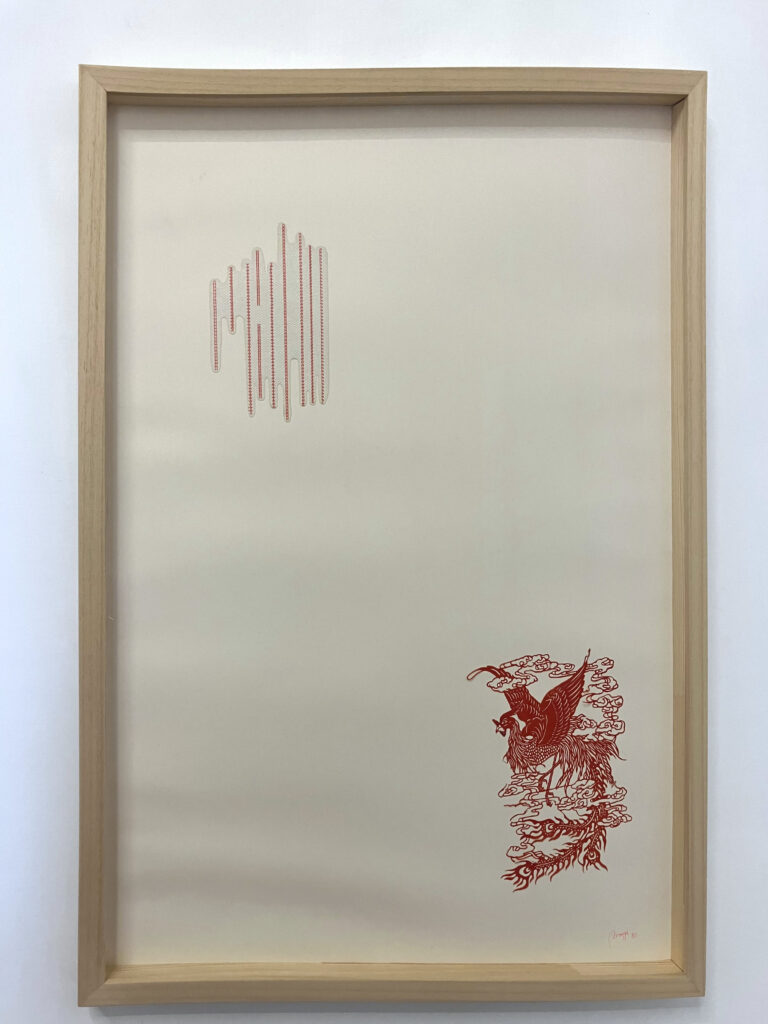

In the late 1970s, a spirit of exploration led her to use a mechanical tool: the typewriter, with which she developed the Dattilocodice [Typercode]. One day, by pure chance, she overlapped two different graphemes, creating an entirely new sign. The original characters are no longer recognizable and take on a completely different and new meaning. The result, although not immediately decipherable, is revolutionary, as it represents a recovery—or invention—of a linguistic archetype through technology.

In the 1980s, Binga continued to assert that “writing” does not necessarily mean “describing,” yet her mark evolved to embrace a more pictorial dimension. In the Biographic series, writing expands, grows in scale, vibrates and becomes colorful. The subjects are large letters that impose themselves on surfaces, often wallpaper, appearing as figures in their own right.

In the 1990s, writing and painting intersect once again in the series Scripta Picta and Scritture catodiche [Cathodic Writings]. Here, writing spreads across diagonal trajectories, interrupted by bursts of color—intense chromatic epiphanies: writing, through osmosis, becomes painting (Tomaso Binga).

If in the 1970s Binga was fascinated by the typewriter, the same happened a few decades later with the computer. The Alphasymbols recall the Dattilocodice, but instead of overlap, they are built on the systematic repetition of symbols, forming square compositions. The continuous stream of identical elements—the almost obsessive persistence of fingers on the same computer key—creates a paradoxical disorientation, one that confuses perception of the symbol itself. It becomes a case of semantic saturation, which once again leads us back to the idea of silent writing.

Tomaso Binga is an Italian artist and poet, born in Salerno in 1931. Since the 1960s, she has lived and worked in Rome. She adopted a male pseudonym as a way of ironically and provocatively challenging the privileges of the male-dominated art world. Her practice focuses on visual-verbal writing and she is a leading figure in Italian phonetic–sound–performative poetry. Since 1971, the practice of art as writing has been at the center of her interests. Her work spans collage, typewritten text, painting, and performance.

Her work has been exhibited at the Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona (1977), Venice Biennale (1978), Biennale of São Paulo (1981), XI Quadriennale, Rome (1986), Fondazione Prada, Milan (2017), Mimosa House, London (2019), Venice Biennale (2022), Fondazione Dalle Nogare, Bolzano (2022), La Galerie in Noisy-Le- Sec, France (2023), Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, (2023).

Currently, the Fondazione Donnaregina per le arti contemporanee – Museo Madre is hosting her most comprehensive museum retrospective to date, titled Euforia Tomaso Binga, curated by Eva Fabbris with Daria Kahn, exhibition design by Rio Grande.