3 Exhibitions to See in January

Our guide to exhibitions in Italy

06.01.2026

In Roman mythology, January is symbolized by Janus, the protector of beginnings and transitions. He has a torso and two faces looking in opposite directions: beginning and end, entrance and exit, before and after. He marks a change while, at the same time, suggesting continuity, because he remains whole and unbroken; his torso supports both heads.

In January, one often feels the need to devote oneself to lists, resolutions, new planners, and calendars, because it seems essential for human beings to measure time, to establish the “when” of things even before the “why.”

The three exhibitions selected this month raise questions that originate in the more or less recent past but keep interrogating the present, in a continuity that never stops flowing.

They suggest widening our gaze, looking beyond the boundaries of what we consider safe, because there are places where the past repeats itself undisturbed, with no deity to intercede. They ask us to reconsider our concepts of right and wrong and to question our systems and hierarchies of values. Finally, they invite us to embrace the indefinite, the abstract, the conceptual—where time does not exist, and possibilities can be infinite.

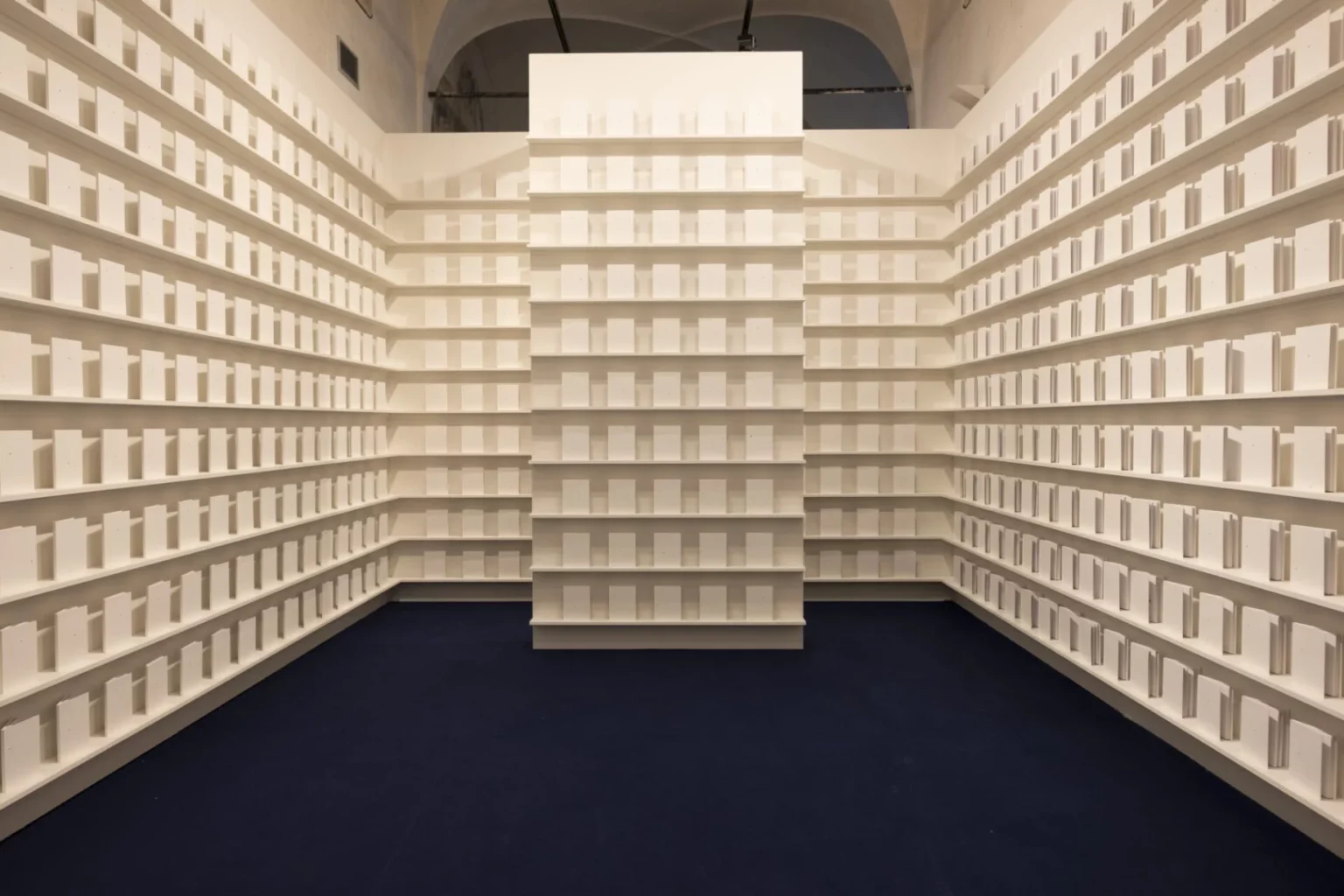

Material of an exhibition. Stories, Memories and Struggles from Palestine and the Mediterranean - Fondazione Brescia Musei (until 22 February)

Emily Jacir, Material for a Film, Fondazione Brescia Musei. Photo Alberto Mancini

The artists at the center of the exhibition at the Museo di Santa Giulia actually come from the margins: Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon—places of conflict dismembered by the Western gaze and by an oblique, fragmented narrative.

The title of the project curated by Sara Alberani tells a story of blood while also paying homage to the work that concludes the exhibition, Material for a Film by the Palestinian artist Emily Jacir: one hundred books with blank pages, each struck by a bullet, evoke the copy of One Thousand and One Nights that the Palestinian poet Wael Zuaiter carried in his pocket on October 16, 1972, in Rome, when he was assassinated by Mossad. The book—a symbol of Arab literature, which Zuaiter had intended to translate into Italian—was perforated by bullets along with the poet’s body.

The exhibition asks whether it is possible to find in the visual arts a means of active resistance against policies of oppression, acts of intimidation, repressive practices, and white colonialism. Aware that solitude is a silent permit for the dismantling of communities, the voices of Mediterranean artists instead act as a binding force, in an attempt to recover—or preserve—that integrity which makes dialogue and exchange possible.

Alongside Jacir’s works—an internationally acclaimed artist awarded the Golden Lion at the 2003 Venice Biennale—Mohammed Al-Hawajri and Dina Mattar exhibit pieces salvaged from the bombings of December 2023 in the Gaza Strip, while All of the Lights by the Lebanese artist Haig Aivazian investigates structures of power within contemporary society.

Among the first exhibitions in an Italian public museum dedicated to the Palestinian context, Material for an Exhibition speaks in different languages—installation, video, photography, painting, and drawing—but all the artists involved express, without exception, the same refusal to disappear.

Body Sign. VALIE EXPORT e Ketty La Rocca - Thaddaeus Ropac, Milan (until 28 February)

Body Sign. VALIE EXPORT e Ketty La Rocca, Thaddaeus Ropac, Milan, exhibition view. Photo Roberto Marotti

Ketty La Rocca and VALIE EXPORT never met, yet their artistic practices traveled along parallel tracks. They didn’t need to speak to each other; it was enough to inhabit the same world for a few decades—not that many, given that La Rocca died at just 38 from a brain tumor in 1976.

One in Florence and the other in Vienna, for both of them art coincided with a fierce struggle against the traditional linguistic system and a profound rethinking of the female body in urban space: “The dominant language was a form of manipulation. The plan was to circumvent these forms of social control. […] This was the power of the female body: being able to express itself directly, without any mediation.”1

The immediate awareness for both was that they could not work on a single front but, on the contrary, had to incorporate as many media as possible. Performance, film, sculpture, video, and photography all contribute to attacking on multiple fronts a centuries-old system based on binary thinking, definition, and exclusion.

From TOUCHCINEMA, a performance in which EXPORT invites the audience to touch her breast through an open box, to La Rocca’s “alphabetical presences”—black sculptures of letters and punctuation marks that highlight the limits of verbal language—and to her video work Appendice per una supplica, in which two pairs of male and female hands convey the power of pure gesture, free from any verbalization, up to the work that gives the exhibition its title: in Body Sign, VALIE EXPORT photographs herself while exposing her thigh, with a garter tattooed exactly where a real garter would be worn.

These are works that use sarcasm to challenge the system, politics, and the art world, expressing a feminism that is angry yet lucid, detached, and analytical—where blind emotion does not prevail, but logic as a form of dissent does.

The exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac’s Milan location—opened in September—finally allows the two artists to meet, touch, and speak in a language entirely their own, the one they helped shape through their tireless and stubborn research. What they communicate, beyond words, remains their secret.

Turcato - Fondazione Giuliani, Rome (until 31 January)

Turcato, Fondazione Giuliani, Roma, exhibition view

A single color: through the monochrome, Giulio Turcato was able to speak of proliferation, abundance, genesis, and growth. In pure color, there is room for everything—nothing else is needed. It is enough to let the surfaces breathe, to make them alive and throbbing, to make them move imperceptibly.

The Mantuan painter, one of the most inventive of the postwar period, intertwined political commitment with formal research, rejecting—along with his colleagues, and one female colleague, Carla Accardi, from the Forma 1 group—the realism and figurative rigor of Communist art in favor of a free and emancipated abstraction. His canvases are spaces where the essentiality of color coexists with the complexity of the viewer, who receives it, listens to it, almost swallows it into its depths. The observer falls into it without protection, but the impact is gentle, the surface soft and kind. Color embraces rather than repels, creating spaces of listening in which one can find what one is seeking: peace, doubts, monsters.

Less material and restless than Alberto Burri, less scientific than Enrico Castellani, for Turcato “the monochrome is never a final destination, but rather a beginning”2—it does not serve to provide answers but to awaken new questions. It is an active field of investigation, where things happen, where flowers grow, water boils, and a match lights. It is not a theoretical ground, but a deeply practical zone, aimed at activating, setting in motion.

For Turcato, two elements are enough to contain the universe: color and form. After all, this is what the world is made of.

________

1 VALIE EXPORT, “VALIE EXPORT,” interview by Devin Fore, Interview Magazine, August 24, 2012

2 Dal press release