Why Write About Art

Clicca qui per leggere la versione italiana

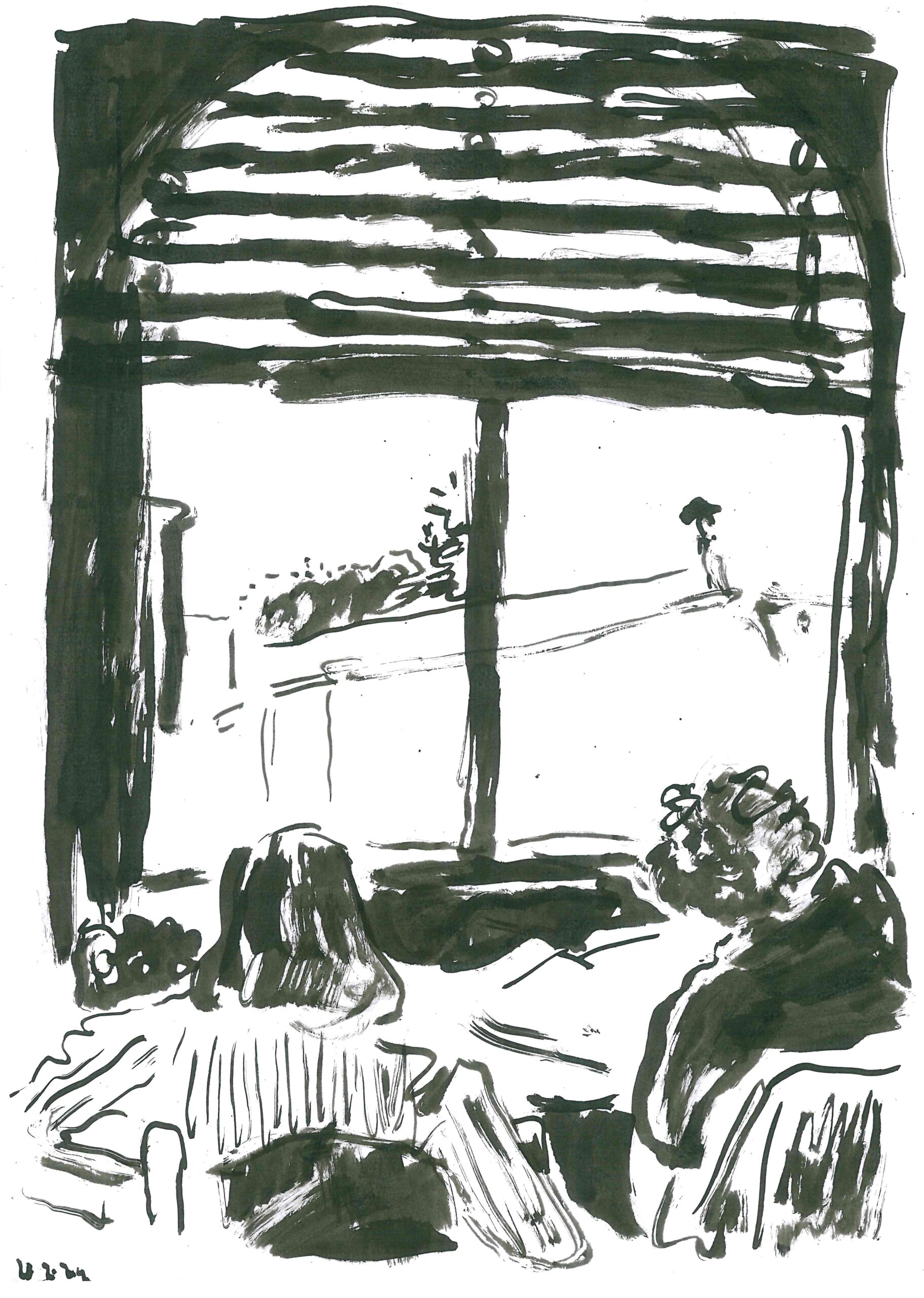

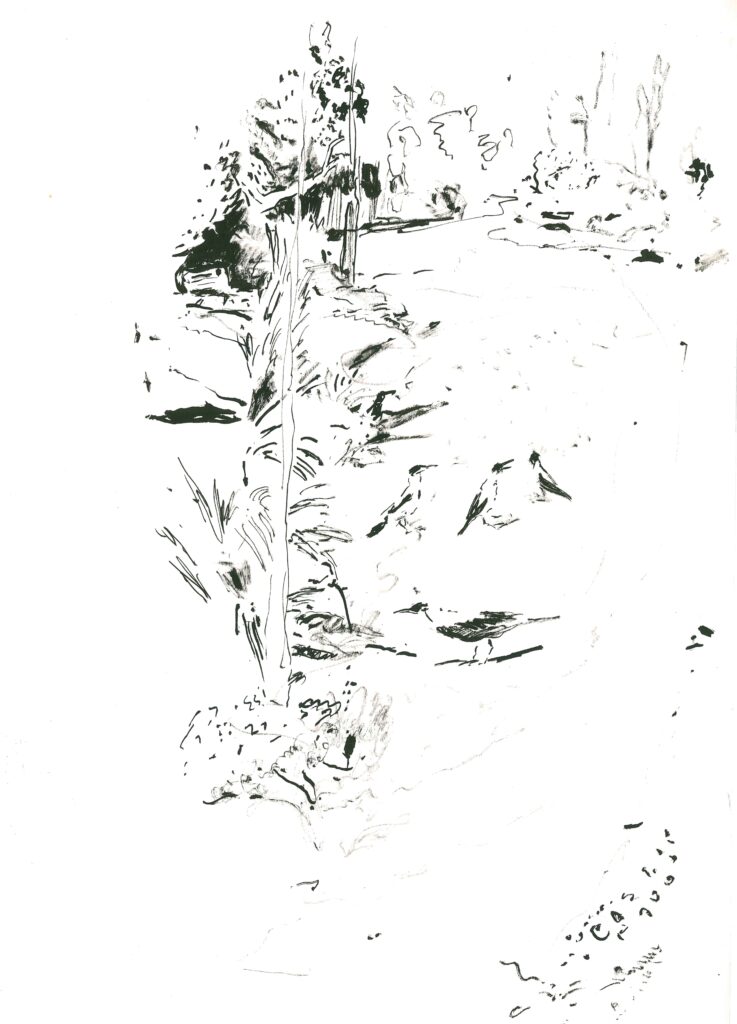

When we read words about art, we are often immediately captivated, as we are not only guided through the observer’s gaze but also invited to reflect on what their memory and thoughts have grasped and embraced. In this sense, writing—particularly writing on art — differs from other forms of authorial trace in its ability to offer a perspective and an interpretation of meaning for something that has endured and been irrevocably consigned to language. Therefore, asking, “why write about art today?” is essential, not only to examine the condition of contemporary art criticism, but also to reveal how each era views art differently. For this reason, I believe it is necessary to begin the collection of writings titled Offbeat with the drawings of painter Giulio Catelli (b. 1982, Rome), together with the question that gives this first text its title and that may remain unresolved throughout subsequent publications, eventually transforming in unexpected ways.

It is certainly of considerable importance to examine those who, in the past, analyzed art with a critical and historical lens, laying the foundations of art historiography. This allows us to highlight the contemporaneity of different historiographical models, their mutual influences, and even choices that run counter to prevailing trends. And it is precisely this trajectory that enables us to grasp how critical writing functions today. In particular, the study of these methodological approaches has fostered a specific sense of belonging that continues to characterize the discipline and the proposals for change that emerge from it. Certainly, assessing artists and their works through an investigative lens is a process of inquiry and patient accumulation of knowledge, grounded not only in the methodologies adopted by earlier critics but also in archival sources and the method of their research. What is common to writing about art is the urgency to penetrate the spirit of the works by studying their style, structure, and affinities, moving beyond disciplinary boundaries and fostering the convergence of diverse forms of knowledge, while analyzing the contexts of their creation in order to investigate the full scope of their creative framework. In this way, the initial question gives rise to a further one: how can one write about art if not by transforming writing into a practice of knowledge and interpretation, while avoiding a merely documentary approach? To orient writing toward a pure form of inspiration, it is necessary to consider each word not only as a bearer of meaning and knowledge, but also as a tool capable of revealing and, why not eliciting unease.

All of this unfolds through the use of a language open to the persistent search for questions, which are set in motion and intertwine in the face of the unsuspected depth of reality. If speculative experience reveals a cathartic and liberating function, then writing must likewise do so, engendering a poetic lightness devoid of all weight, in order to return to the true nature of the simple and pure word, understood as nourishment for the soul. Therefore, if contemporary art today is a creative phenomenon that arises and perpetuates itself, it must be understood all the more within a comprehensive framework. For these reasons, it is appropriate that the artist’s research be explored, studied, and revealed through a mode of writing that maintains clarity of exposition, without necessarily yielding to a reassuring interpretation of the work. According to these aims, one should not write in order to assert one’s own intellectual authority, but rather to truthfully articulate a variant of it.

In the operational dimension, writing requires keen, nuanced clarity of vocabulary, demanding a clear understanding of what one wishes to convey. Like a tool in contact with the most silent and profound aspects of art, language presents itself as a smooth, continuous surface, where each point emerges distinct from the others, as if it were the simplest, most comprehensive, and intuitive thing that could exist. Thus, in Offbeat, writing must be the result of an authentic bond with the artist, the space he inhabits, and the artwork itself, so that it remains autonomous and uninfluenced by any prior knowledge that might standardize it. At this stage, one must consider whether this form of writing is motivated by a desire to safeguard the work or, in aiming to sensitize the public, also involves revealing its imperfections and uncertainties. This is the most sensitive aspect of critical writing, which—born from a profound relationship with the artist and serving as a tool for truthful inquiry—makes it essential to conduct uncompromising analysis, probing even the seemingly least significant factors. Yet today, aside from sporadic cases, critical writing lacks the capacity to combat widespread cynicism, careerism, and the paralyzing sense of emptiness that prompts us to reinvent ourselves with courage. Those who dare, fly; those who do not try, achieve nothing. Similarly, the critic, like the artist, must be aware that, in reality, performing one’s work is equivalent to designing and writing a flight manual, a tool that allows the artwork to come alive and unleash infinite possibilities of interpretation.

Reading, looking, and treating doubts as prompts for reflection are all actions that lead us to perceive works through a perspective that is both slowed down and speculative. Writing becomes a pause, a moment of deep reflection aimed at revealing what captures our gaze, how much focus we devote to observing, and the narratives we draw from it. For this reason, I chose to accompany this first publication with the works of Giulio Catelli, because, just like the writings in Offbeat, his approach to painting is rooted in a strong and sincere expressiveness. In this way, all the questions posed in this first essay seek to explore how writing dedicated to art is received, lived, experienced, and preserved in memory. So, in response to the question, “Why write about art?”, the answers may be many: we write to build relationships and strong bonds, to steal time from reality, to transgress conventions, to fulfill desires, to fight against any tendency toward indifference, and certainly to relinquish any comforting certainty.

Maria Vittoria Pinotti

Translated to English by Dobroslawa Nowak